The Social Media Folk #

Users fuel social media by creating and sharing content, participating in discussions, and engaging with other users. As a result, they help shape online conversations and determine the direction and tone of discussions. Users can also advocate for causes, businesses, or organizations by sharing information and promoting their work on social media. Ultimately, the role of users in social media is to connect, share ideas, and create a sense of community online.

Consequently, the number and activity of users substantially determine the value of a social media platform. Personal data represents significant value to digital platforms, serving as an input to algorithmic targeting or as a general revenue stream. Proposals to share data-based revenue with consumers have emerged due to concerns about the potentially unequal distribution of this value between data owners (the platforms) and data subjects (the users). For example, California Governor Gavin Newsom has proposed a “data dividend” to compensate consumers who create online footprints1. Academics have argued that users’ online data should be considered “labor” and paid accordingly2. A recent study looked at how much consumers value their data on Facebook and how their valuations change based on real-world informational interventions2. They found that the median Facebook user values their data at $750.

One reason for the sloppy handling of data could be that many people are unaware of what happens to their data. For example, it is now common for companies to analyze and exploit online behavior for advertising purposes3.

Emotions, Feelings & Firestorms #

We can (and most of us do) express emotions, feelings, and moods on social media. Social media platforms provide users with a convenient way to express themselves through text, images, and videos. For example, someone might use a social media platform to express their happiness at a friend’s wedding or to share their frustration on a bad day (i.e., Monday).

Emotions, feelings, and mood are all related psychological states, but they differ in some important ways. Emotions are intense, often brief, and typically involve a physiological response. They are triggered by a specific event or stimulus and generally focus on a particular object or situation. For example, if you see a cute puppy, you might experience joy.

Feelings, on the other hand, are the conscious experience of emotions. They can also include more complex psychological states such as love or jealousy. Unlike emotions, feelings are more diffuse and less tied to a specific stimulus. For example, you might feel happy without necessarily having a particular reason.

Mood, meanwhile, is a more general psychological state that can encompass emotions and feelings but is less intense and more long-lasting. Moods are typically less tied to specific events or stimuli. Instead, they can influence a person’s overall emotional state for an extended period. For example, you might be in a good mood after having a great day at work, or you might be in a bad mood after experiencing a series of frustrating events.

Overall, emotions, feelings, and mood are all related psychological states. However, they differ in intensity, duration, and the specific triggers that cause them. Social media can also influence a person’s emotions, feelings, and mood. For example, seeing posts from friends and family that make them happy can improve a person’s mood, while seeing posts about a controversial topic can trigger strong emotions. Social media can also support people who are feeling down, as they can connect with others who are going through similar experiences (see social contagion).

Sentiment, Valence, and Positivity #

Sentiment, valence, and positivity are all related concepts in psychology and are often used to describe people’s emotional states. Sentiment refers to a person’s overall emotional state or attitude. It can be positive, neutral, or negative and is typically expressed through language or behavior.

For example, if someone says “I love this product,” that would be a positive sentiment. Valence, on the other hand, refers to the positivity or negativity of an emotion. It is typically measured on a scale, with positive emotions having a high valence and negative emotions having a low valence. For example, joy would have a high valence, while anger would have a low valence. Positivity, meanwhile, refers to a general tendency to experience positive emotions and attitudes. People who are positive tend to be optimistic, hopeful, and happy, and often have a good outlook on life.

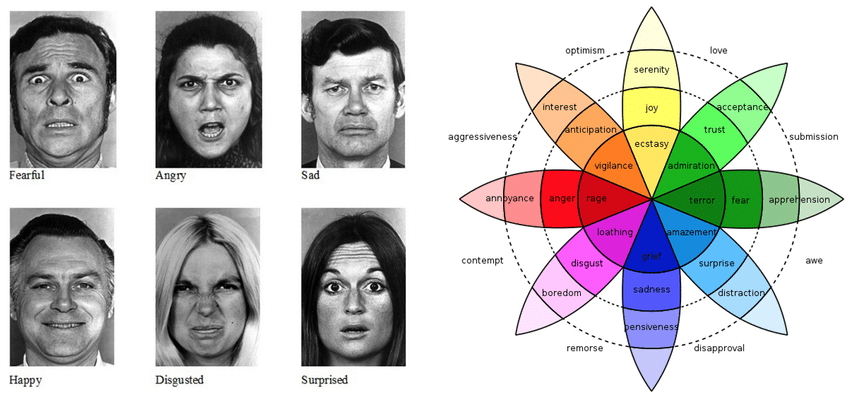

It is hard to define whether people experience the same emotions in everyday life, as it is a very personal experience that observers can’t simply measure. Quite frankly, the same emotions can be felt in many different ways and intensities, depending on education, the cultural differences that humans grow up in, and many other factors. In his previous research, Paul Ekman understood that there are six distinct human emotions, the so-called basic emotions that can be observed because of the facial expression that every human makes while feeling them. He started this research to study patients who claimed they were not depressed and later committed suicide4.

Emojis #

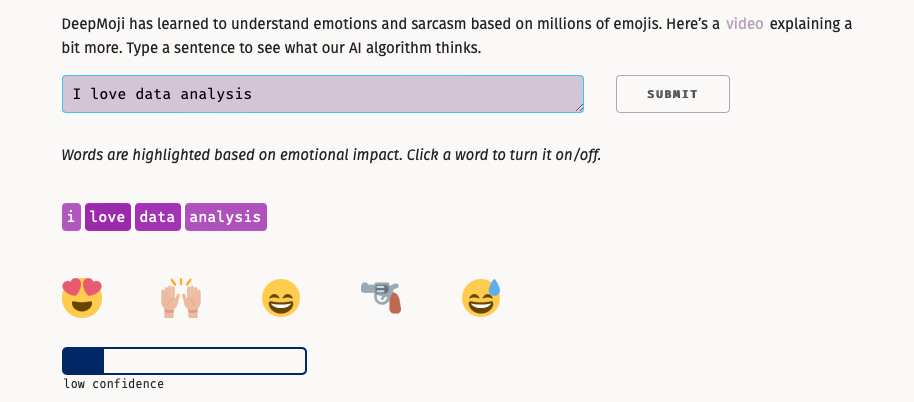

Emojis are small digital images or icons used to express an idea or emotion in electronic communication. They originated in Japan, and the word “emoji” comes from the Japanese words for “picture” (e) and “character” (moji). Emojis are often used in text messages, social media posts, and other forms of online communication to add personality and context to written messages.

These pictograms come in a wide range of styles and can depict a wide variety of objects (e.g., 🎄), animals (e.g., 🐶, 🐰), and emotions (e.g., 😡). Some common examples include the smiling face emoji, the heart emoji, and the thumbs-up emoji. Emojis represent things like food, sports, and activities. In recent years, emojis have become increasingly popular and are a common feature of many electronic communication platforms. They are often used to add tone and emphasis to written messages. Consequently, people use them as a playful or humorous way to communicate.

Basic emotions #

Basic emotions are a group of primary emotions that are universal across cultures and are thought to be biologically innate. These emotions include happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. They are called basic emotions because they are thought to be the foundation for more complex emotions, and are often triggered automatically in response to certain stimuli. The concept of basic emotions was first proposed by psychologist Paul Ekman, who conducted research on the facial expressions of emotions4 5. He found that people from different cultures and backgrounds consistently showed the same facial expressions when experiencing certain emotions, suggesting that these emotions are universal and not culturally specific.

Basic emotions are thought to be important for survival, as they allow people to quickly and automatically respond to potentially dangerous or rewarding situations. For example, fear can help people avoid danger, while happiness can motivate them to seek out pleasurable experiences.

In contrast, Plutchik proposes a wheel of emotions to describe emotions6. In essence, it is a visual representation of the various emotions that people can experience. The wheel is typically circular in shape, with different emotions arranged around the circumference. Moreover, it is divided into different sections, with each section representing a different category of emotions, such as basic emotions, complex emotions, or social emotions. The emotion wheel can be used as a tool for understanding and identifying emotions, and can also be helpful for people who are trying to express their emotions in a healthy and constructive way.

Ekman does not support the theory of the emotion wheel. He believes that the list mentioned above of well-established basic emotions are the only “real” emotions that exist, and he, therefore, he sees other emotions as “not-real” emotions5. Ekman lists several criteria for basic emotions, and he believes that everything that meets these is real emotions provided by evolution.

**In-class task** Please try our Nade-Explorer. This tool allows to infer emotional intensities from even short textual messages. Link: **[https://short.wu.ac.at/nade-explorer](https://short.wu.ac.at/nade-explorer)**

Social Influence, Diffusion & Virality #

Social influence, diffusion, and virality are related concepts that describe how information, ideas, and behaviors spread within a group or society.

Social influence is how others influence people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It can take many forms, such as conformity, obedience, persuasion, or peer pressure. Social influence is a powerful force in shaping people’s attitudes and behaviors and can positively and negatively affect individuals and society.

Diffusion, meanwhile, refers to the process by which information, ideas, or behaviors spread from one person or group to another. This can happen through various channels, such as word of mouth, media, or social networks. Diffusion is a crucial aspect of social influence, as it helps transmit information and ideas from one person or group to another, enabling them to impact people’s attitudes and behaviors.

Finally, virality (or social transmission) refers to the rapid and widespread spread of information, ideas, or behaviors within a group or society. This can happen through social media, online networks, or other forms of electronic communication and can lead to a sudden and dramatic increase in the popularity or awareness of a particular idea or phenomenon. Virality is often a sign of the power of social influence and diffusion, indicating that a specific idea or behavior has resonated strongly with many people. The virality of content depends on the properties of the content, such as emotion7. For example, sharing behavior depends on evoked levels of valance and physiological arousal8. In particular, positive and arousing content (e.g., awe) is more viral than negative and low levels of arousal (e.g., sad content)9.

Social influence, diffusion, and virality are related concepts describing how information, ideas, and behaviors spread within a group or society. They are essential in shaping people’s attitudes and behaviors and can significantly impact individuals and society.

Influencers #

A social media influencer can (and does) influence the behavior or opinions of their followers. Influencers can be broadly categorized based on the size of their follower base into micro, macro, and mega-influencers10. Professional influencers often partner with brands and businesses to promote products or services, and they are typically paid (ergo professional) for their endorsements. Some social media influencers focus on a particular niche or interest, while others have a more general audience. Social media influencers can generally leverage their online presence and influence to create business opportunities for themselves and the brands they work for. Empirical evidence shows that people are more likely to buy a service if their social media friends did already done so11.

There is a controversy around an influencer’s reach (in terms of the number of followers). While higher reach allows influencing more people, it may have downsides (e.g., lower authenticity or weaker connection to the follower base)10. Authenticity, in particular, is often discussed since there is already empirical evidence showing that influencers adapt their content to optimize their income12. Moreover, the impact of peer-to-peer influence on service adoptions seems to be less pronounced for influencers with a higher number of friends11. In addition, a study on Twitter has shown that the virality of posts is not significantly determined by the size of the author13.

Moreover, we see “herding effects” in liking behavior 14. Previous ratings lead to a significant bias in individual rating behavior, and positive and negative social influence leads to asymmetric herd effects. While negative social influence cause users to correct manipulated ratings, positive ones increase the probability of positive ratings and lead to a herd effect that increases final ratings.

In contrast, the susceptibility to be influenced depends heavily on demographic factors. For example, research conducted on Facebook reveals that younger users are more susceptible to influence than older ones. Moreover, men are more influential than women, women influence men more than other women, and married individuals are the least susceptible to influence in the decision to adopt the product offered15.

Social ties #

Social ties are relationships or connections between individuals or groups. They can be strong or weak, and the strength of a social tie is determined by the amount and quality of the interactions and exchanges between the individuals or groups involved16.

Frequent, intense, meaningful interactions and exchanges characterize strong social ties. They often involve close personal relationships, such as those between family members or friends. They can be based on shared values, interests, or experiences. According to social tie theory, the strength of a person’s social ties can significantly impact their attitudes, behaviors, and well-being. Strong social connections provide several benefits, such as emotional support, social support, and resource access. They can also act as a source of social influence, shaping people’s attitudes and behaviors.

On the other hand, weak social ties are characterized by infrequent, superficial, or impersonal interactions and exchanges. These can include acquaintances, coworkers, or casual acquaintances and are often based on more limited or specific interactions. As a result, weak social ties are less important for providing support and advice. However, they can still play a role in spreading information and forming social networks.

Social tie theory indicates that weak ties provide more new information 17. Most network models deal implicitly with strong ties, thus confining their applicability to small, well-defined groups. Emphasis on weak links lends itself to discussing relations between groups and analyzing segments of social structure not easily defined in terms of primary groups.

A study found a moderating effect of tie strength and structural embeddedness on the strength of peer influence by randomly manipulating messages sent by adopters of a Facebook application to their 1.3 million peers18. Moreover, weak ties also impact sharing behavior by increasing job transmissions on LinkedIn19. In addition, when personal networks are small, weak links have a more pronounced impact on information dissemination than strong ones16.

Social contagion #

Social contagion is a phenomenon in which certain behaviors, emotions, or ideas spread quickly and easily from one person to another through social networks and interpersonal interactions. It is a form of social influence that can occur within a group of people or a population as a whole. Contagion and influence are related but distinct concepts. Contagion refers to the spread of behavior, emotion, or idea from one person to another through social networks and interpersonal interactions. Influence, on the other hand, refers to the ability to shape or alter the thoughts, behaviors, or attitudes of others. While contagion often involves some form of influence, it can also occur without conscious intent or awareness. For example, an anxious person may unknowingly transmit their anxiety to others simply by being around them. However, a marketing campaign that uses persuasive messages and imagery is a more deliberate attempt to influence people’s behavior or attitudes. Social contagion can be positive or negative, depending on the transmitted behavior or emotion.

For example, a study based on Facebook data found that exercise is socially contagious and varies with the relative activity of and gender relationships between friends 20. Less active runners influence more active runners, but not the reverse. Both men and women influence men, while only women influence other women.

An emotional contagion is a form of social influence in which people unconsciously mimic the facial expressions, body language, and behaviors of those around them, leading to a shared emotional experience. Emotional contagion can have both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, it can help people connect and bond. It can also lead to increased cooperation and coordination within a group. However, on the other hand, it can also spread negative emotions and behaviors, such as aggression or anxiety.

Early research on emotional contagion examined this question by conducting a field experiment on Facebook that analyzed the behavior of users after posts with emotional content were removed from their timelines 21. The objective of this experiment was to determine if exposure to emotional content on social media leads to similar verbal expressions. One group of users had positive posts withdrawn from their timelines. The other group had posts with negative emotions removed. The results confirmed that contagion could occur without direct interaction or non-verbal cues. Therefore, users experience the same emotions they see in posts without awareness. Additionally, the study observed that the withdrawal of emotional posts resulted in less activity on the social media platform. Online messages influence our experience of emotions, which can impact our offline behavior in many ways.

Similar behavior was observed in a study focusing on emotional contagion caused by viral videos and Internet memes22. This experiment examined whether videos are forwarded more often when they evoke a strong emotional reaction in people. Several videos were selected that were supposed to trigger either positively or negatively perceived emotions, and a few videos were expected to appear emotionally dull to viewers. The results confirmed the initial hypothesis that participants who viewed videos evoking positive emotions were significantly more likely to forward those videos. Different underlying arguments can explain these results. On the one hand, people tend to deliver videos that they perceive as positive because they generate a more robust affective response. On the other hand, sharing positive content results in people wanting their friends and family to experience the same pleasant emotions.

Another study measured the emotional contagion on Twitter23. The researchers found that positive emotions are more prone to contagion among users. Furthermore, compassionate people are much more likely to adopt positive emotions. However, the paper also states that it is challenging to distinguish emotional contagion from empathy. In some cases, users may pretend to feel sympathy, even if they do not necessarily do, by matching their expressions with the content shared by others. Moreover, users with social roles of opinion leaders are usually more influential than ordinary users in positive emotional contagion24. At the same time, they are less influential regarding negative emotional contagion.

A study on emotional contagion in massive social networks estimated that the contagion of emotional expression indicates that there may be widespread spillovers across online networks25. What people feel and say in one place can spread to several parts of the world on the same day. Their results suggested that emotions can move through social networks to create large-scale synchronicity leading to clusters of happy and unhappy individuals. An earlier study developed the “SISa model of infection”. It formally demonstrated that emotions could be seen as contagious diseases that spread across social networks26.

Various studies and experiments support the hypothesis that emotions can be transferred online without direct interaction. In particular, positive emotions in posts or videos generate stronger reactions, influencing how we behave online and in real life. However, it may be challenging to reveal all the underlying dynamics behind emotions and contagion in future studies.

Collective emotions #

Collective emotions are those experienced by a group in a specific context or situation. They arise in many different settings, such as at sports events, during political rallies, or in response to a natural disaster or other crisis. In these situations, people’s emotions can synchronize and amplify each other’s emotional experiences, leading to a shared emotional response.

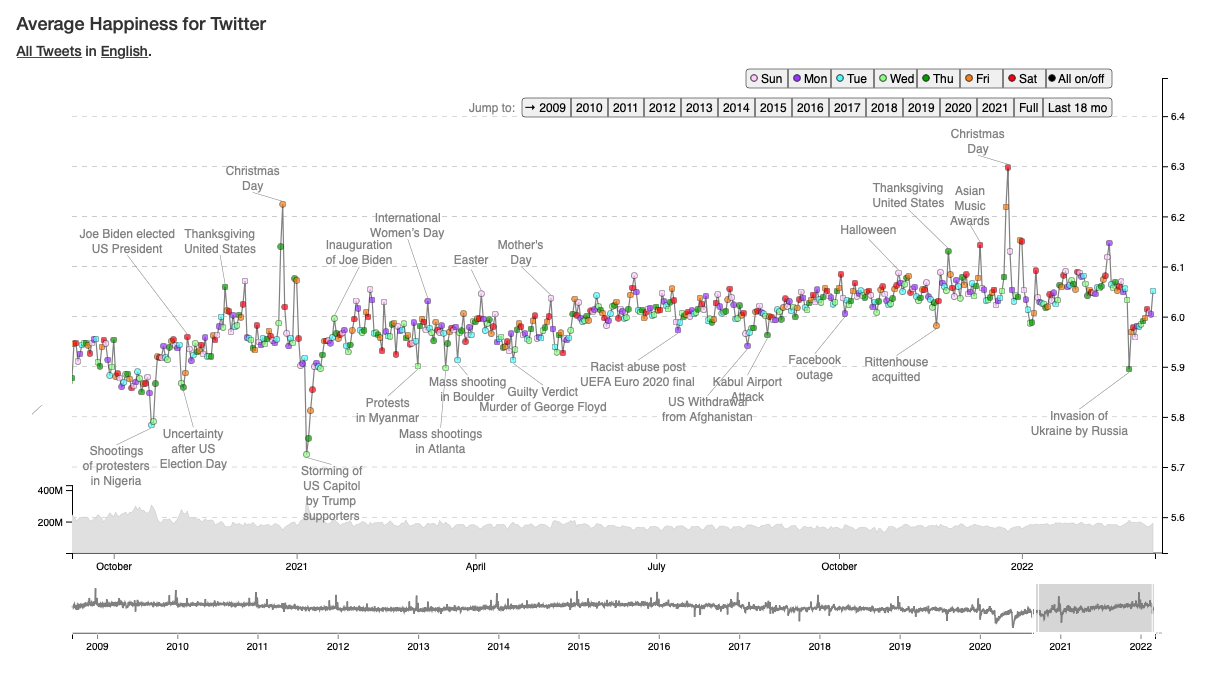

Collective emotions occur in “real life” and online communities where many users can share their emotional states. However, in contrast to the real world, people who use social media platforms can quickly reach many other users. Moreover, external events, such as natural disasters and endogenous causes like discussions in online forums, may release millions of users’ online expressions of emotions27.

**Example:** An imposing example of the impact of collective emotions on social media is the so-called Blackout Tuesday movement. It brought a big wave of protests against racism and is seen as one of the most prominent digital protests these days. It all started with two musicians who responded to the death of the African American rapper George Floyd which resulted during a police operation. Celebrities like Kylie Jenner, Justin Bieber, and Katy Perry followed by posting empty black pictures on their Instagram profile with the hashtags #blackouttuesday or #blacklivesmatter. Since then, many private individuals have also participated in online protests on Twitter and other social media platforms.

Collective emotions can have significant impacts on group behavior and decision-making. For example, they can influence people’s willingness to engage in certain behaviors, such as participating in a protest or supporting a particular cause. They can also affect people’s perceptions of other individuals or groups. They can shape social norms and values within a community.

Challenges #

Although social media has been around for decades, there are increasing challenges from a user perspective. These include platform dependency, but also social pressure and issues such as online shaming.

Online shaming #

The emergence of social media platforms has dramatically changed social justice enforcement. While an offender would be displayed and humiliated in a public location in the past, the shaming has now shifted to the online world. Mass availability and access combined with anonymity allow “everyday citizens” to enforce social norms through social media profiles. However, this can have catastrophic consequences for those at the receiving end. In hopes of providing insights that could be of value in understanding this “re-emergence” of public shaming, this elaboration tries to give an overview of online shaming and explores the different forms.

Online shaming is publicly criticizing or condemning someone on the internet for their actions or beliefs. It often involves using social media and other online platforms to spread information or accusations about the person, damage their reputation, or cause embarrassment or distress. It can take many forms, such as posting negative comments or reviews about someone, sharing embarrassing or private information, or organizing a social media campaign against them. In addition, it can be motivated by various factors, such as a desire for revenge, a need to express anger or frustration, or a belief that the person has done something wrong.

The consequences for the people involved are manifold. They comprise the public backlash, reputation damage, and loss of support or opportunities. It can also have broader social impacts, fueling political polarization and social division.

## Practical assignment I SQL-prerequisites: [SELECT](https://duckdb.org/docs/sql/query_syntax/select)-Statement, [ORDER BY](https://duckdb.org/docs/sql/query_syntax/orderby)-Clause, [LIMIT](https://duckdb.org/docs/sql/query_syntax/limit)-Clause, [WHERE](https://duckdb.org/docs/sql/query_syntax/where)-Clause In this practical example, the handling of databases shall be learned. The following questions all refer to a table called *youtube_tweets* (please import it as we did in the first session). This table contains Tweets that contained a YouTube link and were posted in Germany or German in December 2022. Besides the text, the table comprises information about the author and the tweet. Use the [DuckDB Shell](https://shell.duckdb.org) to answer the following questions: - How to show all the columns of the first 5 rows of the table sorted by ascending _created_at_? - Which tweet (_id_) has the most replies (_reply_count_)? - How to list the date/times (created_at) of tweets posted by rexel_id (_username_)? - How to show the tweets (_text_) with more than 10.000 likes (_like_count_)? - How to show the tweets (_text_) with more than 10.000 likes (_like_count_)? and more than 100 replies (reply_count)? Please submit your SQL-query as well as a short and precise textual answer via Learn@WU. - [Slides: Introduction to SQL](https://slides.inkrement.ai/sql/intro)

References & further reading #

- Slides: The Social Media Folk

- Berger, J. (2016). Contagious: Why things catch on. Simon and Schuster.

- Berger, J., Humphreys, A., Ludwig, S., Moe, W. W., Netzer, O., & Schweidel, D. A. (2020). Uniting the tribes: Using text for marketing insight. Journal of Marketing, 84(1), 1-25.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-12/california-governor-proposes-digital-dividend-targeting-big-tech ↩︎

Collis, A., Moehring, A., Sen, A., & Acquisti, A. (2021). Information Frictions and Heterogeneity in Valuations of Personal Data. Available at SSRN 3974826. ↩︎ ↩︎

Boerman, S. C., Kruikemeier, S., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2017). Online behavioral advertising: A literature review and research agenda. Journal of Advertising, 46(3), 363-376. ↩︎

Ekman, P. E., & Davidson, R. J. (1994). The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press. ↩︎ ↩︎

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & emotion, 6(3-4), 169-200. ↩︎ ↩︎

Plutchik, R. (1980). A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In Theories of emotion (pp. 3-33). Academic press. ↩︎

Akpinar, E., & Berger, J. (2017). Valuable virality. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(2), 318-330. ↩︎

Berger, J. (2011). Arousal increases social transmission of information. Psychological science, 22(7), 891-893. ↩︎

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral?. Journal of marketing research, 49(2), 192-205. ↩︎

Park, J., Lee, J. M., Xiong, V. Y., Septianto, F., & Seo, Y. (2021). David and Goliath: when and why micro-influencers are more persuasive than mega-influencers. Journal of Advertising, 50(5), 584-602. ↩︎ ↩︎

Bapna, R., & Umyarov, A. (2015). Do your online friends make you pay? A randomized field experiment on peer influence in online social networks. Management Science, 61(8), 1902-1920. ↩︎ ↩︎

Sun, M., & Zhu, F. (2013). Ad revenue and content commercialization: Evidence from blogs. Management Science, 59(10), 2314-2331. ↩︎

Bakshy, E., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Everyone’s an influencer: quantifying influence on twitter. In Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining (pp. 65-74). ↩︎

Muchnik, L., Aral, S., & Taylor, S. J. (2013). Social influence bias: A randomized experiment. Science, 341(6146), 647-651. ↩︎

Aral, S., & Walker, D. (2012). Identifying influential and susceptible members of social networks. Science, 337(6092), 337-341. ↩︎

Goldenberg, J., Libai, B., & Muller, E. (2001). Talk of the network: A complex systems look at the underlying process of word-of-mouth. Marketing letters, 12(3), 211-223. ↩︎ ↩︎

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American journal of sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380. ↩︎

Aral, S., & Walker, D. (2014). Tie strength, embeddedness, and social influence: A large-scale networked experiment. Management Science, 60(6), 1352-1370. ↩︎

Rajkumar, K., Saint-Jacques, G., Bojinov, I., Brynjolfsson, E., & Aral, S. (2022). A causal test of the strength of weak ties. Science, 377(6612), 1304-1310. ↩︎

Aral, S., & Nicolaides, C. (2017). Exercise contagion in a global social network. Nature communications, 8(1), 1-8. ↩︎

Kramer, A. D., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788-8790. ↩︎

Guadagno, R. E., Rempala, D. M., Murphy, S., & Okdie, B. M. (2013). What makes a video go viral? An analysis of emotional contagion and Internet memes. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2312-2319. ↩︎

Ferrara, E., & Yang, Z. (2015). Measuring emotional contagion in social media. PloS one, 10(11), e0142390. ↩︎

Yang, Y., Jia, J., Wu, B., & Tang, J. (2016). Social role-aware emotion contagion in image social networks. In Thirtieth AAAI conference on artificial intelligence. ↩︎

Coviello, L., Sohn, Y., Kramer, A. D., Marlow, C., Franceschetti, M., Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2014). Detecting emotional contagion in massive social networks. PloS one, 9(3), e90315. ↩︎

Hill, A. L., Rand, D. G., Nowak, M. A., & Christakis, N. A. (2010). Emotions as infectious diseases in a large social network: the SISa model. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1701), 3827-3835. ↩︎

Von Scheve, C., & Salmella, M. (Eds.). (2014). Collective emotions: Perspectives from psychology, philosophy, and sociology. OUP Oxford. ↩︎